3 books this month, which made for plenty of reading but not a very long reading log. Nevertheless, there was plenty to think about and write about. Take a look!

4 Articles I Like This Month

"Integrity and the Future of the Church" by Russell Moore, Plough. 17 minutes.

A sobering, insightful look at what is driving so-called "ex-vangelicals" to leave the church...it's not them, it's us.

"The Passion of Questlove" by Jazmine Hughes, The New York Times Magazine. 24 minutes.

A profile of the always fascinating D.J., audiophile, and frontman for the Roots.

"I Had a Chance to Travel Anywhere. Why Did I Pick Spokane?" by Jon Mooallem, The New York Times Magazine. 22 minutes.

The author, prepared to enter post-pandemic life, attended a minor league baseball game. What did her learn from the experience about America?

"The Afterlife of Rachel Held Evans" by Eliza Griswold, The New Yorker. 17 minutes.

A profile of one of my favorite Christian writers, the late Rachel Held Evans, in preparation of the release of her posthumous memoir.

Reading Through the Fantastic Four- #175-193, Annual #12

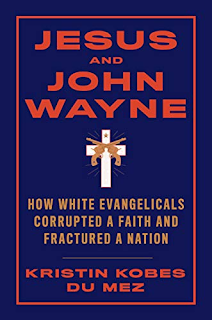

JESUS AND JOHN WAYNE: HOW WHITE EVANGELICALS CORRUPTED A FAITH AND FRACTURED A NATION by Kristin Kobes du Mez

Many have remarked in the last 5 years that American evangelicalism seems to be more of a sociopolitical movement than a religious one, more grounded in subculture than theology. Articles, blog posts, speeches, and endless pontificating by pundits have decried how different the American evangelical church looks from the one Jesus established in the first century. But few have told the story of how this came to be. Jesus and John Wayne, a seminal work by history professor Kristen Kobes du Mez, tells that story persuasively and powerfully.

According to du Mez, American evangelism emerged as a mixture of biblical theology, Christian nationalism, southern heritage, and masculine militancy, and can trace its birth to the early days of the Cold War. It was in that time, with the looming threat of Communism top of mind, that American Christians, insecure in the face of a changing world, began looking for security in the kind of men exemplified by the characters played by John Wayne: rugged defenders of law and order. None of that is particularly novel—people have always turned to strongmen in times of fear. What was new was the way the church began to gradually baptize this archetype.

Moving chronologically from Billy Graham to Jerry Falwell to Oliver North to the cast of Duck Dynasty to, finally, Donald Trump, du Mez convincingly shows how key figures came to exemplify (some intentionally, some unwittingly) this movement and how, by 2016, being an "evangelical" had come to mean something much different from "Bible believing Christian" even as most evangelicals maintained they were synonyms.

Ultimately, du Mez postulates, what today drives American evangelicalism as we know it is fear—fear of change, fear of being reduced or replaced, fear of an unknown future. What's left to the next generation, if we are to turn the ship around, is to remind people that perfect love casts out fear. As du Mez puts it in the book's final sentences, "Appreciating how this ideology developed over time is also essential for those who wish to dismantle it. What was once done might also be undone."

MIDDLESEX by Jeffrey Eugenides

Hooooo boy. Going to have to be careful how I write this review.

That's because Middlesex, the winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, is a coming-of-age novel about a hermaphrodite, a.k.a. an intersex individual, someone who is born with both characteristics of both sexes and cannot be classified in a binary sense. Dealing with issues of sex and gender, the book is ahead of its time in many ways (though, for those deeply enmeshed in the LGBTQ+ community, I suspect it is considered retrograde in other senses). And for those almost totally unfamiliar with these topics <raises hand timidly> it is an education and, like all great novels, an exercise in empathy.

But, as you might guess about an award-winning novel, it is not confined to one topic. In fact, the book is equal parts family saga, immigrant novel, and coming-of-age story, while also having a good deal to say about America (specifically Detroit) in the 1950s through 1970s. To be more specific, it tells the story of Cal (initially Calliope) Stephanides and her struggle growing up with the secret, suspected but not entirely understood, that she is intersex. As Cal tells his story, he takes it all the way back to the scandalous marriage of his grandparents in Greece and their immigration to America, as well as the meeting and marriage of his parents and ultimately Cal's own birth.

Throughout the book, several themes dominate: shame, acceptance, and ultimately, redemption. By telling his family's story, Cal comes to terms with his own; by grounding his identity in his family story, he is able to make sense out of the confusion he was born into.

Jeffrey Eugenides is a masterful writer (this was my second of his novels, and far superior to the other, The Marriage Plot), and manages to pull off the literary feat of telling a complex, thematic story without ever seeming pretentious or overly intellectual. While the plot of this book is worlds away from what I'd normally read, his engaging prose and relatable characters hooked me early. For those willing to listen and learn, to put yourself in the shoes of someone whose experience you know nothing about, I recommend Middlesex. It'll stretch you, to be sure. But sometimes we need that.

ESSENTIAL GHOST RIDER VOL. 1 by VariousMy impression going into this Essential volume, the first of four on this character, was that Ghost Rider is a fantastic design in search of a character. After reading his first 20+ issues, I stand by that assessment.

There is no doubt, Ghost Rider looks cool. I mean, look at that image above. A leather-bedecked motorcycle rider with a flaming skull for a head? That's just awesome, especially when his cycle has flaming wheels (not pictured above, but quickly made a feature of the character.) It's for good reason that Ghost Rider's design has barely changed at all in the 40+ years since his introduction.

But as for the character and his stories, this volume shows that Marvel knew they had visual gold long before they had any narrative to match. While the origin would later be retconned more than once, Ghost Rider's basic origin comes down to a deal with the devil, a deal struck by stunt rider Johnny Blaze (yep, that's his real name) in order to save his mentor and the father of his girlfriend. In exchange for the sparing of that life, Blaze becomes an agent of darkness, transformed every night (and then in a later retcon, whenever danger lurks) into a hellfire-wielding demon.

It's actually not the worst premise, just one that never really goes anywhere, at least not in this volume. As depicted by a rotating cast of Marvel's Bronze Age writers, Ghost Rider is little more than an Evil Kinevil ripoff, an undisguised attempt by Marvel to cash in on that 1970s craze. The character doesn't acquire any memorable villains in his first few years, his support cast is so boring that he ends up stealing someone from Daredevil's (Karen Page briefly joins Blaze's stunt crew), and the character as a whole feels utterly directionless. For a character who looks so dynamic, it's amazing how boring his book really is.

Ghost Rider's early stories betray the danger of when comics rush something out. With a design like Ghost Rider's on the cover, comic readers were always going to give this book a shot. But if I'd been there in the 1970s, it wouldn't have taken me long to give up on the book. Great visuals will get you started in comics, but they can't be the only thing you have going for you.