I like months where the reading selections are varied, and once you see which 5 books I read this month, I think it's safe to say that you'll agree I unlocked the 'variety' achievement level. Take a look!

3 Articles I Like This Month

"There's a Name for the Blah You're Feeling: It's Called Languishing" by Adam Grant, The New York Times. 7 minutes.

The pandemic has left so many people—myself included—in a strange state of mental health. If you find yourself walking around in a fog, often lacking motivation or drive, and dealing with a nagging undercurrent of anxiety, this article gives that feeling of "blah" a name: languishing. I can't recommend this article enough.

"What the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Destroyed" by The New York Times. 12 minutes.

In this interactive feature, the staff at the New York Times used historical documents and 3-D rendering to both illustrate and describe the Greenwood neighborhood known as "Black Wall Street" which was burned to the ground in 1921 by a lynch mob in what remains one of the most destructive acts of domestic terrorism in our nation's history. A sobering, haunting look at what white supremacy took from the black community.

"'I Feel Like I'm Drowning': Sophomore Year in a Pandemic" by Susan Dominus, The New York Times. 53 minutes.

It remains to be seen how the pandemic will affect Gen Z long-term. But this article, which follows the lives of a handful of students and their teacher over the course of the last school year, gives an idea.

Reading Through the Fantastic Four- #75-93, Annuals 6 and 7

If last month's reading of the Stan Lee-Jack Kirby run on FF was the pinnacle, this month's was the twilight, a stretch of issues that are good, sometimes great, but never legendary. Indeed, with the exception of Annihilus (a bug-like tyrant from the Negative Zone) and Reed and Sue's son Franklin, no new characters are introduced in this stretch of issues. By this time Lee and Kirby's partnership, which once had a Lennon-McCartney-esque magic, had reached its Let It Be stage—professional but cold, with the two acting as solo artists in the same band rather than as true partners.

The most notable thing to happen in this stretch of issues is the aforementioned birth of Franklin Richards and the subsequent induction of Crystal into the Fantastic Four (first to take Sue's place during her pregnancy and then during the first few months of motherhood.) I'd like to say Crystal adds a lot to the team, but instead she is largely forgotten, relegated to the sidelines at least as often as Sue was in the early days of the FF. As for Sue herself, she is reduced to a wide-eyed, constantly hysterical caricature—Stan Lee always had a weak spot when it came to writing female characters, and he's never worse than here in that respect.

As for Kirby's art, it remains in tip-top shape at first, but by 1969 (around issue #80) you can see him taking shortcuts. The fire and passion are gone, and behind the scenes he's looking for the back door. It's still better than 90% of the comic art out there, then or now, but it hardly matches the heights of his earlier work in the mid-1960s.

Next month the Lee-Kirby partnership comes to an end as the pair hands the reins to Roy Thomas, John Buscema and Company and the Silver Age of the 1960s gives way to the 1970s' Bronze Age. See you then!

THE PURPOSE DRIVEN CHURCH by Rick Warren

Most churches today run on tradition and personalities, the mixture of systems set up long ago and the tireless effort of a small cadre of staff and volunteers. These churches exist largely to benefit their members, and there is a constant, nagging fear that they are only a few deaths away from going up in smoke entirely.

In 1995's The Purpose Driven Church, megachurch pastor Rick Warren presents a different model for ministry, one that argues that a church should be built around its ends rather than its means. By finding its purpose and building everything around that purpose, a church can flourish and become what God always intended for the church to be: a light to the world.

The Purpose Driven Church is the kind of book that will get a pastor fired up quickly. Its diagnosis of the typical church's problems is just as accurate today as when it was published 26 years ago, and Warren's solutions (both his broad prescription and the more detail-oriented suggestions along the way) have the ring of truth to them. I found myself nodding along a lot while reading, and often had to put the book down to make notes to myself about how to apply its principles.

With that being said, the book isn't flawless. Warren has been a megachurch pastor for decades now, and some of his solutions—while appropriate for a large church in Orange County—just don't work in Garland, Texas. For example, he argues that ministry should be done by church members and maintenance by church staff, i.e. that the day-to-day things like fixing broken water heaters and sending announcement emails should be done by paid staff so that members can get to the more important, divinely mandated work of evangelism and community service. While I love that principle, what do you do if your church can't afford more than a couple of staff members? What if the entire staff is bi-vocational? Financial flexibility is routinely taken for granted by Warren, and it's simply not a reality for most churches.

My second criticism is one common to church growth books, which is that the book treads dangerously close to being a guide to salesmanship and customer service instead of gospel ministry. While I firmly believe Warren's heart is in the right place, some of his views on worship—like that it should be about drawing in "seekers"—may grow a church, but are biblically sketchy. My primary desire is to be faithful to God's will; sometimes it appears the church growth movement's is to draw a crowd.

Those reservations notwithstanding, this is an excellent book, one I'd certainly recommend to pastors seeking to battle inertia in their congregations and set a vision for the future. Take some of Warren's principles with a grain of salt, but don't ignore what he has to say here. Because ultimately he's right: the church should not be driven by tradition, it should be driven by its purpose.

THE CROSS AND THE LYNCHING TREE by James H. Cone

Jesus was publicly humiliated, beaten, and executed in order to satisfy a mob who saw him as a threat to the existing social order. Jesus, says black theologian James H. Cone in this seminal work, was lynched.

That reality is one that has guided black theology in the United States for 400 years. Black Christians have turned to Jesus for solidarity in their own struggles and have found hope in the idea that suffering can be redemptive, that God can transform even the vilest of sins into something that blesses the world. For black Americans, the connection between the cross and the lynching tree borders on self-explanatory and is never far from mind.

Sadly, for white Christians that connection is often either ignored or rejected. Guided by a sense that things are better now than they used to be, white Christians are extremely uncomfortable whenever it is suggested that what happened to Jesus is strikingly similar to what our forefathers were still doing to black Americans as recently as two generations ago. Some of the 20th century's greatest theologians, men who spent decades looking at the cross from every conceivable angle, somehow never acknowledged the terrifying resemblance between the cross and the lynching tree.

Cone, who spent a lifetime studying and articulating black theology, gave a gift to the world in The Cross and the Lynching Tree, a slim, popular-level primer for the subject he spent his career studying. As a historical work, it examines the history of lynching in the United States, from slavery to Emmitt Till. As an insight into black theology, it details the ways that black Christians have found truth and power in the gospel in spite of and because of the oppression they have suffered. And as a word to white Christians, it serves as an education, rebuke, and warning that the lynching tree is not something that can be forgotten or ignored. The Cross and the Lynching Tree is a powerful, prophetic word to the church, and should be required reading for any Christian who believes in racial reconciliation.

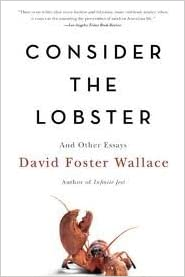

CONSIDER THE LOBSTER AND OTHER ESSAYS by David Foster Wallace

I have two dueling thoughts about David Foster Wallace's writing, both of which guided my reading of this essay collection.

The first is that Wallace was an insightful, observational writer with a unique voice. Whether writing about something as seemingly dull as grammar, as in "Authority and American Usage," or as inherently fascinating as an insurgent presidential campaign, like in "Up, Simba," there is no mistaking who the writer is and what talent he possesses. Fluent in both academese and Midwestern common sense, Wallace can get in the weeds of literary minutia one minute only to speak fluently for and as the common man in the next. In essays like "Consider the Lobster," which sees him touring a lobster festival and asking about the morality of our boiling an animal alive, his morality and intelligence are both on full display and yet he never gets preachy. David Foster Wallace had a gift for writing and a style all his own.

But that style, as I was reminded throughout my reading, can be exhausting. His obsession with footnotes (most famously in his magnum opus, Infinite Jest) has a way of making you constantly lose the flow of the writing and often feels too cute by half. Some of his essays (like the aforementioned one on grammar and another, "Big Red Son," about the adult film industry) seem to be twice as long as they need to be. The feeling when you finish a Wallace piece is not only one of satisfaction, but relief.

It is the first, positive thought that has prompted me to buy and read a lot of Wallace's writing (2 novels, 1 short story collection, and this essay collection.) When I am removed from reading Wallace for a while, I remember his genius and it lures me in. But it's the latter thought that makes me leave him on the shelf for months. David Foster Wallace, it turns out, is a lot like this story's titular lobster...delicious, but not something you can have every day.

SUPER SONS OMNIBUS by Peter J. Tomasi, Jorge Jimenez, Patrck Gleason, Carlo Barberi, et al.

Ok, first a little background information for the uninitiated.

Since 2006, Robin has been Damian Wayne, the love child of Batman and Talia al Ghul. Raised by Talia in secret, Damian grew up among the League of Assassins and at age 13 is already one of the world's most gifted martial artists and detectives. Upon meeting his father, Damian left his dark upbringing behind and vowed to carry on Batman's legacy. With that being said, Damian is veeeeery thirteen...arrogant, impolite, and generally a pain in the butt. In a talented writer's hands, he's a fun and fascinating addition to the Batman mythos; in the wrong writer's hands he's just obnoxious.

Newer to the hero game is Jonathan Kent, son of Lois and Clark. At age 10, Jon, a.k.a. Superboy, is still getting a handle on his powers and has a lot to learn. But like his father, he brings an infallible earnestness and moral compass to the table, along with a healthy dose of childlike enthusiasm.

In a crossover story in Superman's main title, writer Peter J. Tomasi decided it was time to bring these two prepubescent heroes-in-training together. And from the get-go, sparks flew, with Damian and Jon's personalities immediately clashing in a way that was endlessly entertaining and that reflected their parents' attitudes without simply mimicking them. Robin and Superboy bickered their way to victory, and the Super Sons were born.

This omnibus collects all the adventures of the pair, beginning with that crossover and continuing through the entire run of the resulting Super Sons title. First they take on Kid Amazo, a teenager infected with a virus giving his body the powers of the Justice League even as it eats away at his mind. Next they team up with the Teen Titans (of which Robin is a member) to take on a time-traveling villain. Their final series of adventures comes courtesy of Rex Luthor and Joker Jr., a pair of pint-sized villains from another dimension.

But truthfully, the plots aren't the highlight or even the point of this pairing. It's all about watching Robin and Superboy bounce off one another. Their bickering, unlike the sometimes too-cute-by-half quips of the MCU, never gets old because, well, these are kids. It makes perfect sense that they would be immature and silly.

I've said it before and I'll say it again, comics should be fun. And having a 13-year old assassin-trained Robin team up with a 10-year old Superboy fresh off the farm is fun. This is not high art, but it's certainly worth a look.

SUPERMAN: LAST SON OF KRYPTON by Geoff Johns, Richard Donner, Adam Kubert, Gary Frank, et al.

Superman is famously the only living survivor of his planet's destruction (well, him and Supergirl). But what if there were others?

That's the premise of "Superman: Last Son of Krypton," the lead story in this deluxe hardback collection, a story which sees the arrival of a mysterious Kryptonian boy whom the Man of Steel seeks to protect and nurture. Unfortunately, things are not quite as they seem—the boy, while truly innocent, is the son of the infamous General Zod, a Kryptonian war criminal trapped in the Phantom Zone prison dimension. The boy, it turns out, is something of a Trojan horse, presaging the arrival of Zod and his army of criminals. It is left to Superman (and eventually the Justice League) to defeat Zod and send him and his army back to the Phantom Zone.

The story embraces the Kryptonian side of Superman's heritage, which has always been the half I found less interesting (I prefer the "adopted son of Earth" narrative). What is compelling is the immediate kinship that Kal-El finds with Zod's son—he almost immediately decides that he and Lois will adopt him. Though it lurks under the surface, Superman longs to know someone like him, and in this story he finds that person, if only briefly.

The other stories in here are pretty forgettable. One three-parter sees Superman go to the cube-shaped Bizarro World to take on its titular hero. While Bizarro, a childlike, imperfect clone of Superman, is a fun supporting character, his Opposite Day speaking style gets really old really fast, and three issues was more than I wanted to read. The other stories and features aren't really worthy of mention.

This isn't a must-have Superman book, but any time Geoff Johns gets his hands on a classic DC character, it's worth a look. Give the "Last Son of Krypton" story a read; the rest you can skip.